Vanity Fair, December 1st, 2012.

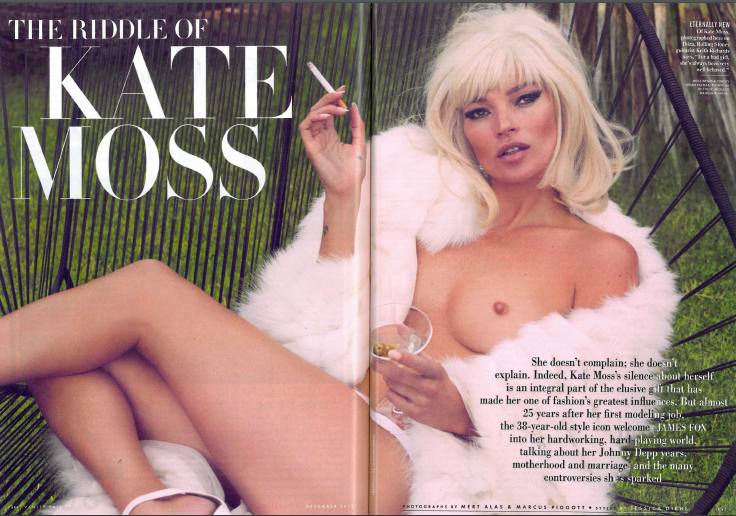

She doesn’t complain; she doesn’t explain. Indeed, Kate Moss’s silence about herself is an integral part of the elusive gift that has made her one of fashion’s greatest influences. But almost 25 years after her first modeling job, the 38-year-old style icon welcomes JAMES FOX into her hardworking, hard-playing world, talking about her Johnny Depp years, motherhood and marriage and the many controversies she’s sparked.

One morning in August, I flew from London to St. Tropez to spend a few days interviewing the most beautiful woman in the world. A tough assignment given that she doesn’t give interviews. At least she hardly ever has, and certainly not about her personal life. It’s nearly 25 years since Kate Moss got her first modeling job, at 14, but this year she agreed, in principle, to talk to Vanity Fair. I imagined she would be guarded. Her silence came partly from the need to not to lay bait for the tabloids, for which she provided a new blood sport in the U.K. But also, she warned me, she’s not interested in being a personnage: “I just live my life, and then I work. There’s a difference between me and what I do.” She didn’t want to “blab,” the way actors and actresses have to do for their movies, about their lives. ‘There’s nothing, really, to say about what I do,” she said. “I just think I don’t want to speak.” It was because I know Moss that I was flying down there. My wife, the fashion designer Bella Freud, has done shows with her and is a friend; I worked with Keith Richards on his memoir, and Moss is more or less a member of his family. Even so, this was different; there were rules and boundaries to be negotiated. Moss said she was up for it – a Moss expression. We would see.

Of all the supermodels of the 1990’s Moss has emerged at the top of the heap, certainly in terms of cultural importance. She’s a style icon, after 25 years, the only one who has continued to model, with no other self-fulfilling diversions or marriages or time-outs, and she is still doing it in more or less the same way she did it when she started, working the same long hours. Last year she earned $9 million – the second highest-paid model in the world, after Gisele Bundechen. At 38, Moss still earns up to $400,000 for a day’s shoot. Along with all that, she has made an art out of having fun, whenever and wherever possible.

Her reticence has created an enigma that has played well in her career. But her life is fascinating. By strange coincidence, the room I had woken up in that morning – as I have done for 16 years – is the room where Moss and Italian-born New York photographer Mario Sorrenti, her then boyfriend, lived in the early 1990s, with a mattress on the floor and little else to furnish it.

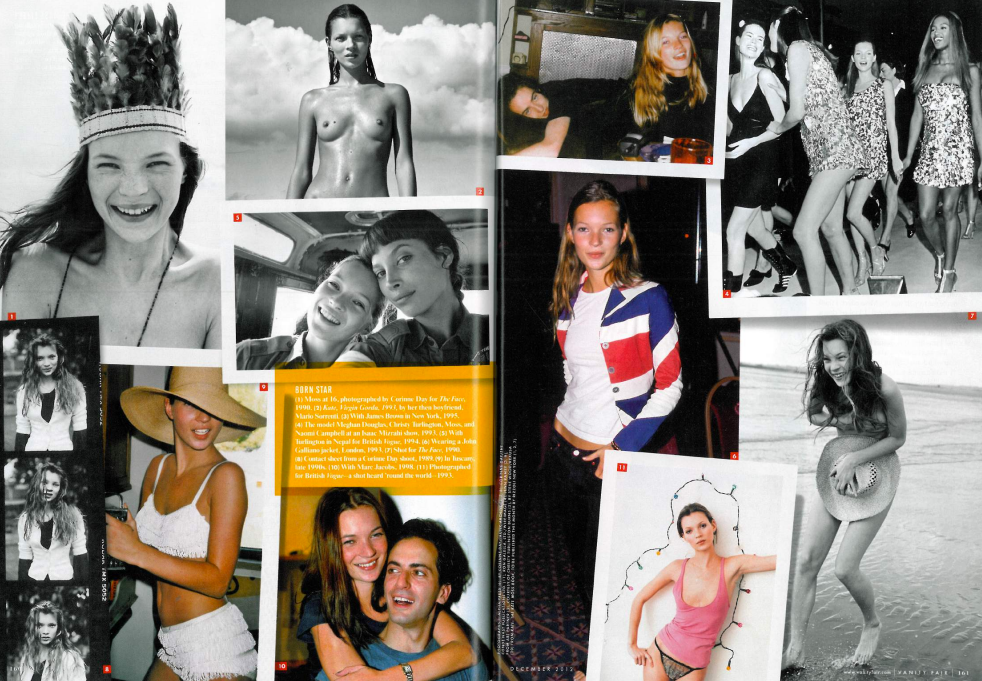

It was against the wall I face when I open my eyes that a picture was taken by Corrinne Day of the young Kate unadorned with makeup, modeling lingerie, with a string of fairy lights behind her. It was part of an eight-page spread in British Vogue in June 1993 that changed fashion forever, and that had the guardians of public safety baying outrage, from the tabloids to the liberal papers. It nearly ended Moss’s career in its infancy. The ironic photograph from that shoot is now part of the permanent collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Moss is billeted on a hill of pines that looks down onto the Bay of Pampelonne to the left and the Bay of St. Tropez on the right. Tall wooden doors open to reveal olive trees and vines, box hedges and gravel. A tail-less dog, part Staffordshire, follows me to the back of the house, where a garden conceals the swimming pool. There, with her 10-year-old daughter, Lila, lying full-length on top of her, is Moss, talking animatedly to her friend Tricia Ronane, who is from Croydon, the London suburb where Moss was born. Warm greetings. I’m reminded that Moss has very good manners. There is time, before she leaves to change, to tell about a party in London after Olympics at her neighbor George Michael’s house. Dancing to his music?, I ask. “Oh, my God! ‘Everything She Wants.’ I was in heaven,” she says.

Then we’re off to lunch at the fashionable Club Cinquante-Cinq, which opened in 1955, when Brigitte Bardot was as famous as Kate Moss and lived around the bay. It’s the first real look I get at Moss’s measured and steady dealings with the frenzy that surrounds her wherever she goes. There is the astonishing level of covert surveillance from adults with iPhones, walking close and pretending not to be filming. For perhaps a minute, as our table was located, Moss stands exposed to rapt attention from the endless tables stretching away under the canvas canopy. She might be alone, waiting for a bus. She appears, quite naturally, not to notice. On the other hand, Moss spots everything, with X-ray eyes, even somehow that someone at the next table with his back to us is wearing a T-shirt showing Moss naked but for a bridal bouquet over her fanny. She gestures for him to turn around, and she laughs. As we walk down a path after lunch, paparazzi rise in a group from behind a hedge, like cardboard figures in a shooting gallery, and then pop down again.

There is much talk of Croydon. “That’s because Tricia’s here,” says Moss. They do some Croydon speak for my benefit – rude stuff, what girls ask girls about boys they fancy, and the proper Croydon pronunciation of the work “cow” in the derogatory sense, as in “stupid caa,” which sounds like “cad” without the d. Moss laughs often – a bewitching laugh. She has a habit of looking at you and cackling silently, mouth in scream position, as in one of her early photographs, head nodding, face creased up, a mannerism that Lila has inherited.

“God, you’ve got a lot of notes,” Moss says to me at one point.

“These are people I’ve spoken to in the last week – James Brown [a hairstylist, Moss’s close friend], Amanda Harlech, Marc Jacobs, John Galliano.”

“Then I don’t have to talk at all, actually!”

“I’m afraid you do.”

“No!”

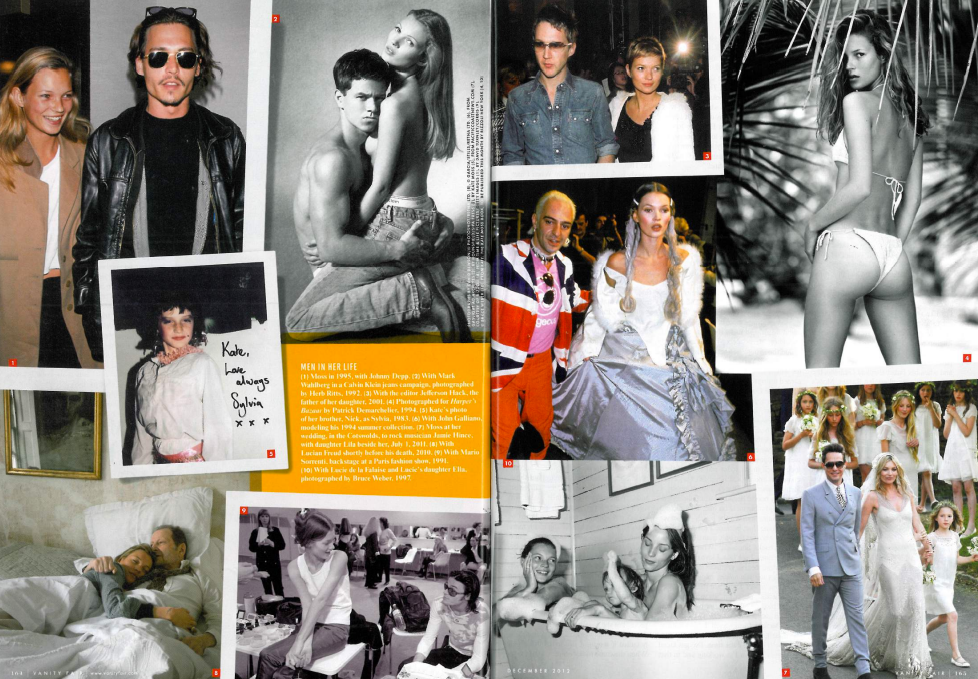

She likes telling, however, of the way you got a look in Croydon, the incubator of her greatness. “I definitely like clothes,” she says. “I used to dress my brother Nick up in looks, as girls. His name was Sylvia. I used to dress him pup and make him come to the door and knock and say ‘Is Kate coming out?’ to my mum. I’ve got a picture of him. He had a beauty spot, fake boobs, and everything – very Liz Taylor. My brother didn’t mind. He found the picture and framed it for me. ‘Kate, Love always, Slyvia.’

My mother was a barmaid, and when I started modeling she was like, ‘Why can’t you just be normal?’ I turned round and said, ‘Why do you think you’re normal?’ It’s that thing of being in suburbia and being crazy, but they don’t think they are. She’d say, ‘You’re not going out like that. Don’t walk down the street smoking. Don’t wear ankle straps. Don’t have a side ponytail.’ In Croydon, if you had those you were common. But that’s all I wanted. Because the cool girls had that. It’s like Lila wants a high bun now, like all the cool girls.”

She continues: “My brother still lives near there, and he doesn’t really go to pubs there, it’s so rough. But it was quite fun growing up there, because it is rough. There’s street stuff going on. Everyone used to hang out in parks and have fights and go to the cinema and have fights. Bit of a fight culture in Croydon. “Was that what you wanted to get out of?, I ask. “I don’t mind a fight,” says Moss. “What I wanted to get out of was the whole thing of, this is it. This is what life is. I never had that feeling of, that’s your lot.”

In her early teens, Moss went to Miami, New York, and San Francisco with her father, who worked for Pan Am. “When I used to come back to Croydon and get into our car, which wasn’t air-conditioned – [a house with] no pool – I was like, I’m not staying here forever.”

The Wild Child

Pulled out of the crowd at J.F.K. Airport by Sarah Doukas, founder of the Storm modeling agency, Moss went to early bookings in her school uniform. Her mother lasted one day, Moss recalls. “She said, ‘That’s it. If you want to do this, you’re on your own.’ I was like, ‘O.K., fine.’”

She hung out, well under-age, at a Croydon wine bar called Rue St. George and drank Snakebite and Black. “Cider, lager, and black currant. They’ve banned it now – makes you go crazy,” she says. James Brown, four years older, spotted her across the room one Friday night. “I turned around and there was this girl, and she just had this long, incredible hair, and she had perfect red lipstick on, and just her giggle and her laugh kind of made me turn. It was the Moss effect. I think she’d just been discovered. I looked down, and she had on these boots that Katharine Hamnett made, and no one else had them, and I was like, ‘Who is this bloody girl?”

She was barely 15 when she went to audition with John Galliano in London, in 1989. “I didn’t mind going up on the train,” she says. I’d never tell anybody at school I was doing photo shoots or anything. I just did it. I was so excited. I don’t know why, but I felt comfortable around those people.”

“It was the show where I showed one of the first bias-cut dresses I produced,” says Galliano. “We were looking for new girls, and she was cast as a wild child. I think she came up to the studio – we were in the New Kings Road – and, wow, I’d found my little rough diamond. She was just amazing – put the dress on, immediately understood what she was wearing, the line, the walk. It was her frock. There was that magic, an enigma, there in front of us. The hair! She had gorgeous long hair. She was a real beauty. But there was more there. She was, even then, quite guarded. I don’t really think that anyone knows who she is today.”

That was Moss’s first meeting with Lucie de la Falaise, another of the “feral girls,” who became Moss’s “sister” and close friend. Lucie is the niece of the late Loulou de la Falaise, the designer and muse of Yves Saint Laurent, Galliano soon discovered that Moss liked to be given a narrative for the dress she was showing.

“Then she lives it in her own way. It kind of gives her a boost. She’s really shy. She loses it sometimes. She thinks, I can’t do it. She knows she can do it. It’s like electricity, and then, boom, she’s out there, and she knows where the cameras are, where the angles are. Very quickly she learned that. She can tell couturiers about the line – what one should be doing, what will and won’t work. And we listen! She is the only real muse I’ve ever had. Actually creative, creating with me.”

Last year, When Galliano was just out of rehab after a moment of insanity, an outburst in a Paris café that led to a criminal charge and banished him from the world of fashion for an unknown time – he was found guilty of “public insults” – and given a suspended fine of $8,500 – Moss stood by him, and he made her wedding dress, by himself, in secret, in France. The old routine still worked. “Mario [Testino] was shooting, and suddenly she just looked at me with those eyes, and it was like, ‘Who am I? What do I do? I need a character,’” says Galliano.

“He’s been talking to me like that since I was 14 years old: “You’re a wild child, and you’re following the boys on the motorcycle-bikes,’” says Moss. “On my wedding day, I’m like freaking out, obviously. And he said, ‘You have a secret – you are the last of the English roses. Hide under that veil. When he lifts it, he’s going to see your wanton past!’” There were wolf whistles for Moss, and when her father thanked Galliano, the congregation stood up. Jen Ramey, Moss’s manager, had wondered about a wedding in a church. “I thought we might all burst into flames, all the crap we’ve done,” she says.

Years back, Galliano and Moss would go to Quiet Storm, a nightclub in St. James’s, in London. Moss got in because she knew the hatcheck girl, Fran Fox, who lived two doors from Moss in Croydon, and at strategic moments she’d hide in the coats. Moss was a fearless 15-year-old, loosely supervised, starting out for London at 11 p.m. wearing “prostitute shoes and crotch minis and not much else. Oh, it was amazing, the best fun ever.

Everyone used to go there – Boy George, Kylie, Michael Hutchence. It was just the coolest place. I stood on Bryan Ferry’s foot, and it was like he was seven foot tall. I’d wear these knee-high leather boots and this tiny little Galliano dress, because obviously it was the only designer thing I had.” Didn’t she have problems in club land, especially dressed like that? “For some reason, I made friends with older people, so they’d always let me in. I don’t know why they always took me under their wing, these guys. It wasn’t a sexual thing, ever. I was really lucky in a way. Sometimes I really fancied them, but they wouldn’t go near me, because I was 15 and they were 19 and stuff.”

Around 1991, she would go on Fridays to an acid-house club called Kinky Disco, on Shaftesbury Avenue, where she would always come in with the same girl, recalls her old friend Bobby Gillespie, the singer in Primal Scream. “I’d seen Kate in The Face [magazine]. I don’t think I ever spoke to her. I think I quite fancied her friend, whose name was Fran Fox.” Moss would stay over with James Brown, who had a flat in Edgware Road. “We’d go to the phone box to ring her mum, and I’d be absolutely paralytic,” Brown says. “She’d be holding me up, going, “It’s O.K. I’m with Jimmy B., Mum. It’s fine!’”

This month, Rizzoli publishes Kate: The Kate Moss Book, which includes photography taken by Corrine Day during the summer. Moss left school in 1990 – a seminal moment in fashion history. They show the freckled, unpainted Moss, running, scowling, standing on the beach, naked or dressed in the simplest clothes, pictures that can still take your breath away with their beauty and raw impact. They appeared in The Face, the street-savvy monthly, as “The 3rd Summer of Love” – a classic statement of the anti-glamorous grunge style, of which Day was a founding artist. It had a direction-changing impact on Marc Jacobs. Two years later he nailed the grunge aesthetic with a famous show in New York, with Moss as a model, for which he got fired by Perry Ellis but earned fashion immortality.

Corinne Day was something of a bully, as well as a perfectionist, and the shoots would last for days, sometimes weeks. “Corinne would make me cry,” says Moss. “I see a 16-year-old now, and to ask her to take her clothes off would feel really weird. But they were like, if you don’t do it, then we’re not going to book you again. So I’d lock myself in the toilet and cry and then come out and do it. I never felt very comfortable about it. There’s a lot of boobs. I hated my boobs! Because I was flat-chested. And I had a bog mole on one. That picture of me running down the beach. I’ll never forget doing that, because I made the hairdresser, who was the only man on the shoot, turn his back.” She adds, “When I see these Face pictures, I see Lila. I love that.”

She describes her grimaces in the pictures as “What are you talking about? Go away! Leave me alone! Those are the things that Corinne really played on. She would say, ‘The more I piss you off, the better pictures I get.’ And I’d just look at her with a look of ‘Hate you!’ Because I was myself. I don’t want to be myself, ever. I’m terrible at a snapshot. Terrible. I blink all the time. I’ve got facial Tourette’s. Unless I’m working and in that zone,

I’m not very good at pictures, really.”

The images also indicate a vulnerability that is still detectable in Moss’s pictures. The subtext of the Moss story, evident between the lines of our conversation, is how remarkably alone and unsupported she was, traveling the world, early in her career. “When I was 15, 16, I was always on my own, and I think that probably made me very vulnerable,” she says. “But I just did it. I’d get in the cab from Croydon, go to the station, to get to Gatwick, to get on a plane to get to work in Paris by nine o’clock in the morning. Imagine! That was before the Eurostar. There was nobody backing me up, really. When I met Lucie’s mum, she kind of took me under her wing. A lot of people have taken me under their wing. Because there wasn’t that much to fall back on. There’s nobody that’s ever really been able to take care of me.” She fell in love with Mario Sorrenti, one of the new wave of photographers, which helped, but they were often separated. He would be in London while she was in New York, where she stayed with his mother, Francesca.

It was in New York, in the early 90s, that Moss became suddenly, at 19, the sole inspiration and focus for a major editorial renaissance in the fashion world. The late Liz Tilberis, the British editor, was relaunching Harper’s Bazaar, with Fabien Baron (co-editor of the new Rizzoli book) as creative director and Paul Cavaco (whom Moss calls “Daddy”) as a key fashion director. They put Moss on an early cover, and in almost every subsequent issue. Baron hired many of the photographers from The Face – Mario Sorrenti, David Sims, Craig McDean, Glen Luchford – who all, says Baron, “wanted to use Moss and only Moss.” Dennis Freedman was the creative director of W as Moss arrived on the scene. “No one expected us to survive,” he says. “We would never have done so without Kate. She was our muse, no question. She was an accomplice. She was a thread throughout those 15 years.” Sam McKnight, the hairstylists, adds, “And suddenly this little, unknown, fresh-faced, scruffy-haired, no-makeup boyish girl appears, with a new breed of photographer, who was taking much more natural light, and it was a new wave, and it kind of changed fashion forever. She became the leader of that, the icon of that.”

Baron was the creative director of advertising for Calvin Klein, who gave Moss an eight-year contract after a single audition – her first big, life-changing contract. Paul Cavaco was consulted as to whether she should sign. “I said, ‘Well, I think she’s gorgeous, but she’s really little. I have a feeling that she may not work a lot.’ So I completely called it wrong. I just loved this child. When she came to my office, I would measure her to see if she’d gotten any taller.”

“She was way shorter than the other models,” says Baron, “with short legs that curved a little bit, teeth not straight and perfect, but with amazing charm.” Moss is five feet seven. After the first Klein campaign – raunchy jeans ads shot with Mark Wahlberg – “waif” became the epithet for Moss’s used to, and it caused a storm of protest.

“I had a nervous breakdown when I was 17 or 18, when I had to go and work with Marky Mark and Herb Ritts,” recalls Moss, who regretted doing the pictures. “It didn’t feel like me at all. I felt really bad about straddling this buff guy. I didn’t like it. I couldn’t get out of bed for two weeks. I thought I was going to die. I went to the doctor, and he said, ‘I’ll give you some Valium,’ and Francesca Sorrenti, thank God, said, ‘You’re not taking that.’ It was just anxiety. Nobody takes care of you mentally. There’s a massive pressure to do what you have to do. I was really little, and I was going to work with Steven Meisel. It was just really weird – a stretch limo coming to pick you up from work. I didn’t like it. But it was work, and I had to do it.”

“Did they think you wanted a stretch limo?,” I ask.

“No,” says Moss. “They were just showing off.”

From This Little Kid to This Creature

Soon she was shooting with Corinne Day again, this time for British Vogue – pictures that launched endless columns of vilification. It was a lingerie shoot, styled by Cathy Kasterine, who had worked for Vogue. Kasterine recalls, “We thought, ‘Let’s do something showing how we all wear our underwear when we’re hanging around the bedroom. You find an old T-shirt, you have a pair of tights, you put your tights over the top. In the context of fashion at the time, and certainly Vogue, it was unheard of. For a beautiful young girl like Kate to appear in such a raw way was: Who is this thin girl? She has no boobs; she has no hips. I think that was the cherry on the cake of people’s reaction against grunge as a movement.”

“The pictures are hideous and tragic,” Marcelle D’Argy Smith, a former editor of Cosmopolitan in the U.K., said at the time. “I believe they can only appeal to the pedophile market. If I had a daughter who looked like that, I would take her to see the doctor.” I show the article to Hannah Lack, deputy editor of Jefferson Hack’s Dazed & Confused magazine, who was 13 when they were shot. “It is so weird reading this stuff,” she says. “I remember loving that shoot so much. Finally, something normal that I could relate to!

“It was very Corinne,” says Moss. “Cheap turquoise – they probably weren’t cheap, but, you know, triangle-shaped knickers, nothing push-up, the kind of underwear that we would wear. But underwear in a girl’s a bedroom and just hanging out, instead of being sexy, was shocking. If it had been a girl with bigger breasts than mine, and what they’d expect to be a lingerie model, then it wouldn’t have been shocking at all. Because it was shot on a teenage girl, they said it was outrageous, pedophilia. Ridiculous. I must have been 19. I’m standing in my underwear. Really controversial.”

Alexandra Shulman, the longtime editor of British Vogue, says, “Everything was hung on this shoot, and on Kate; anorexia, porn, pedophilia, drugs – the evil quartet. One or two maintain that these are still the most interesting pictures we published. I knew they were unconventional, but I never knew there would be this fuss. I would have published them anyway. I thought they looked beautiful.”

Moss was tagged with “heroin chic” as well as anorexia. “I had never even taken heroin – it was nothing to do with me at all,” she says. “I think Corinne – she wasn’t on heroin but always loved that Lou Reed song, that whole glamorizing the squat, white-and-black and sparse and thin, and girls with dark eyes. She loved that look. I was thin, but that’s because I was doing shows, working really hard. At that time, I was staying at a B and B in Milan, and you’d get home from work and there was no food. You’d get to work in the morning, there was no food. Nobody took you out for lunch when I started. Carla Bruni took me out for lunch once. She was really nice. Otherwise, you don’t get fed. But I was never anorexic. They knew it wasn’t true – otherwise I wouldn’t be able to work.” The noise from that shoot has never died down. It furnishes the basic “churnalism” – recycled disapproval, set-in-stone narrative – of the Kate Moss dossier. Churnalism kept alive partly by Moss’s silence.

After she split up with Sorrenti, at the end of 1992, she did get looked after, by fellow supermodels Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington. “I was taken under their wing. They’re like, ‘You’re with us now.’ So much fun! Sleep in the Ritz between Christy and Noami’s room.”

“She did feel kind of lonely,” says Turlington. “She was working so much and so hard and being thrown around the globe in the way that happens to younger models, before they’ve learned to say no. I remember she was wearing her little sneakers and her jeans, and had this little suitcase, and she was very much like, ‘O.K., where am I going tonight? Who am I staying with?’ We were going to go to Dublin to a wedding, and Naomi just grabbed Kate and said, ‘Come with us!’ Naomi would travel with suitcases and suitcases. Kate would have this tiny little bag, with all of these possibilities. She’d have her Galliano Union Jack jacket – that’s what she wore to this wedding. She’d whip that out, and then suddenly Kate was this other person. She went from this little kid to being this creature. Not that long after the weekend in Dublin, within that next year, she met Johnny.”

In New York, in the 90s, Kate Moss and Johnny Depp lived in a building on Waverly Place, where Carolyn Bessette, John Kennedy Jr.’s then girlfriend, lived downstairs. A tribal area was staked out by James Brown, Jen Ramey, the casting director Jess Hallett, and Lucie de la Falaise, the wife of Marlon Richards, who is the son of Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg. They all lived nearby, except Hallett, who would fly in from London for frequent visits. Moss seemed to bind together her proxy family, giving them nicknames and honorary titles – “Jessie Girl,” “Jimmy B.,” and so on. Lucie’s mother was “Mum.” Moss tells me, “Me and Lucie are like sisters, and me and Marlon are like brother and sister. When I met Marlon, we had this weird thing, because he was so uncomfortable in his skin, and so was I, kind of. We were very uncomfortable. And we came from completely different background. His was, like, opposite. My mum and dad stayed in and drank a bit of sherry, and his mum and dad, well, obviously…We bonded immediately.” Keith became Uncle Keith. (Keith’s avuncular testimonial for this article was simply: “For a bad girl, she’s always been very well behaved.”)

And then Moss and Depp parted abruptly, which her friends say affected Moss very badly for a long time. She won’t talk about her exes, saying only this about Depp when we discuss her early life: “There’s nobody that’s ever really been able to take care of me. Johnny did for a bit. I believed what he said. Like if I said, ‘What do I do?,’ he’d tell me. And that’s what I missed when I left. I really lost that gauge of somebody I could trust. Nightmare. Years and years of crying. Oh, the tears!” It was from Depp, however, so her friends say, that she picked up much lasting advice about how to protect her privacy.

The Kate Factor

Moss’s genius in putting together her looks with casual brilliance, as if by luck, and never repeating them has given her huge power in the industry. She tells me she never goes out deliberately to find a new style or a new look. But Bella Freud, working inside a big retailer as a design consultant, describes the walls and mood boards pinned with pages torn out of Grazia magazine of daily sightings of Moss: “Whole clothes lines have been made out of one look she put on one morning.” Responding to that, Moss says, “I know. That’s why I just wear black jeans now. Or gray. If you do a different look every day, they’re going to be waiting for the next look, and then it’s a paparazzi shot. Whereas if you just wear the same thing, then they get bored and leave you alone.”

“Her style is – it’s indescribable,” says John Galliano, “and you can’t work it out. I mean, it’s a huge influence on people. I’ve been to meetings with businessmen sitting around a table with their computers and calculators working out a product, and at the end I’ll say, ‘I don’t know if Kate would wear that.” And they all listen. It’s the Kate factor. And that bag will make it into the collection or not.”

Moss won’t abuse her power, she says. “I would never take over or be bossy. Like Lila is. I would say if it isn’t working, but I’d never take control. I don’t think that’s the role of a model. My part is to make it believeable.”

In the flat on Brewer Street, in London’s Soho, where James Brown and Corinne Day lived, Jess Hallett remembers, “they had this huge wardrobe of charity-shop finds, and Kate and that gang would just pull things out of it and style themselves. An early paparazzi shot of Kate is in a see-through dress that came from that wardrobe.” Scissors were, and are, much used for improvement, according to moss: “I cut up loads. I always want everything shorter, shorter, shorter. Lila had to stop me the other day, cutting a dress up. ‘Mummy, don’t cut it. It looks really nice like that.’ I got Fifi [her personal assistant] to cut a £40,000 coat once. Because it was mid-calf. I can’t do mid-calf. I’ve got bowlegs, so if I do a mid-calf look, I look bandy. I mean, I know my lengths.”

“I do think it’s very innate,” says Anna Wintour, editor in chief of Vogue. “I think it’s an English sensibility that you can throw things together in a way that an American girl can’t, for whatever reason – it’s just not the way they like to dress.

There are a lot of English girls out there that dress like that. Look at the girls in the street – it’s the biggest runway in the world when you go to London. She captures that.”

It was Britishness, perhaps, that inspired Moss to throw together her look for her visit to the notorious KitKatClub, in Berlin. “I’d never been to Berlin before,” she says, “and I loved Cabaret. I just took black and leather. Gloves, shorts, tights, jacket, caps, – I went full-on Berlin. Cabaret-esque. I was doing a shoot for Bazaar. And after the first day, I said, ‘I’m going to the KitKatClub!’ So my driver said, ‘I’ll come with you.’ And he was amazing. I went with him on my own. We got to the door, and there was a big man with a big moustache, and he said, ‘You can’t come in dressed like this.’ And I was like, ‘What do you mean?” He said, ‘It’s S&M night. You can’t come in.’ So I was like, ‘Right.’ I took my top off, got the belt from my leather skirt and put it round my tits, and my driver took his pants off. I was like, ‘You are the best driver in the world.’ And we walked in, and it was pretty hard-core. I got scared. Not scared – I was just like, Maybe this is not…I went up to this man and said, ‘I like your T-shirt,’ and he looked at me funny, and I looked down, and he was wanking. But the club was amazing – the Art Deco on the front of the building, and there’s a big staircase that wraps around the club. It’s all exactly how it was.”

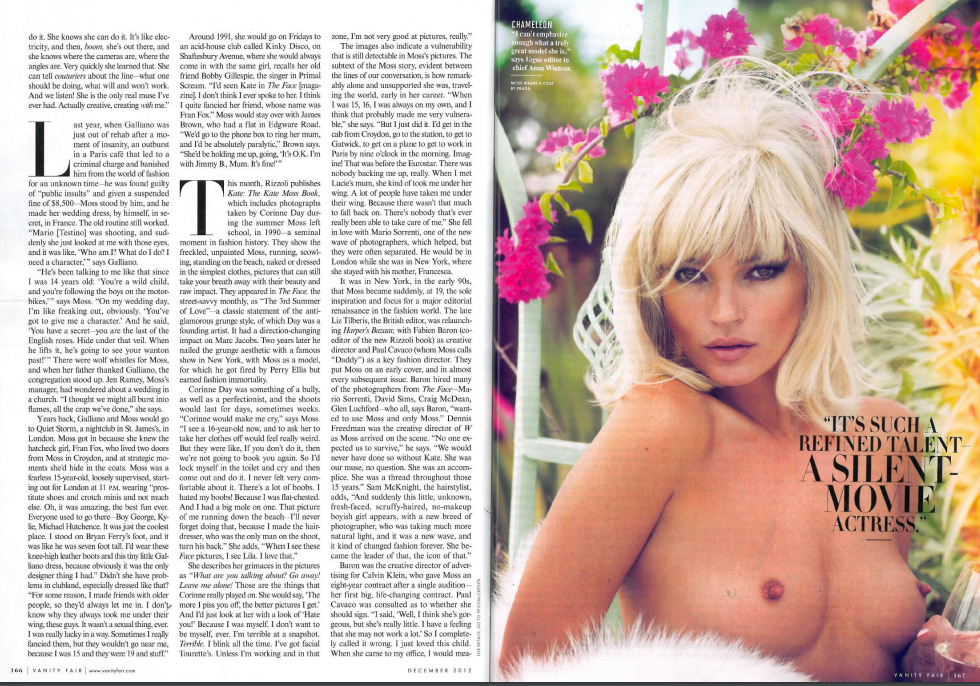

What is the explanation for Moss’s extraordinary fame and survival in a profession many people think slightly ridiculous? “The thing about Kate – and I think it’s part of her longevity – she’s actually quite an elusive girl,” says Wintour. “There’s something quite hidden about her. And I think that’s why so many photographers and editors – and, later on in her career, artists – were always drawn to her. Because it was hard to say exactly what she was or who she was, and they could put their own fantasies onto her. At the same time there was always something a little edgy about her. She was not in any way corporate. She was a little bit dangerous, and that made her exciting and interesting. She can be a chameleon or a sex bomb – so many different things. I can’t emphasize enough what a truly great model she is.”

I ask the British artist Marc Quinn, whose solid-gold sculpture of Moss sat for a while in the British Museum, whether he had divined the secret of Moss’s unflagging fascination after his long contemplation of her form. “Her image is elusive, and you can never fix it,” he replies. “Even if you make it in solid gold, another image will appear. If you think you’ve taken the definitive photograph, you never have. It’s a special quality, which means she continues to carry on and gets more and more mythical. It’s the mystery of the Sphinx.”

“She’s not a model,” says Fabien Baron, “someone who’s just going to model the clothes. She can design clothes. She has an opinion about things. She understands imagery, understands pictures. She’s one of the few people that can turn being a model into a very creative job. She has a talent. She exists today not only because she’s beautiful, but because her personality is on her face and in her movements. It’s her mind that comes across, not the body or the face. When you take the picture, you get so excited!”

“It’s such a refined talent,” says Sam McKnight. “It’s a silent-movie actress, and she’s one of the best silent-movie actresses I’ve come across.”

Nick Knight, the London photographer who has perhaps taken more pictures of Moss than anyone else, says, “There is an engagement between her and the lens which is very believable, which puts her in the company of the great actresses. But there’s always the feeling with Kate, too, that you’re in front of someone you might have known at school, a very odd sense of familiarity, and I’m guessing it was the same with that lot of British photographers that started with her – Glen Luchford, David Sims, Craig McDean. It wasn’t a weird, exotic bird from another land. This was someone who you felt at ease with.”

“When she’s being photographed, she has this animality; there’s almost a tribal, voodoo thing between her and the camera,” says shoe designer Christian Louboutin. “I saw it when Mario Testino was photographing her. She is always moving, and there is a moment when the picture has to be taken, and she’s there in the pose, even if she’s floating.”

“I don’t even know what I’m doing,” says Moss. “It’s an instinct. I mean, there’s a certain breakdown now, after all this time. I can put on a dress, but still I don’t know. Nobody tells you what to do. So I have to feel, without any words, what they want and where the light is, and what the makeup’s doing, and how I’m going to make it work. It is a puzzle all the time, I think. That’s what’s good about it.”

While she’s doing that, says Paul Cavaco, she is exercising “a special thing that separates her. She has this quality of letting you in. When you look at her, you feel like you know her and she knows you. Just from a photograph. You think, I have a relationship with this person. People, when they see her, scream, “Kate! Kate!’”

Getting “Mossed”

There are other clear reasons for Moss’s survival. Her silence is certainly one. As Louboutin says, “She’s been smart in not boringly explaining herself for things not connected with her work. Very few do that. She carries some of the mystery in her face. The super-painful stuff has never been explained. There’s something quite aristocratic about her – every single public, weird story she went through, she never explained, she never complained. She’s a huge example of freedom.”

She has also avoided the trap of branching out into areas where she might do less well. Her collaboration with Philip Green to work for Topshop, the clothing chain, was an exception, and a shrewd business move. Moss, Green confirmed to me, approached him first with the project. Music is the only real temptation for her; most of her partners, current and ex, can play, and she’s done vocals with Primal Scream and videos with such artists as Jack White and, most recently, George Michael, playing the Angel of Death in his video of “White Light.” I saw her perform one night before an audience at a charity fund-raiser at the Café de Paris in London. She sang “Summertime,” accompanied by David Gilmour of Pink Floyd.

It was not recorded, but it was a performance of convicting brilliance, with more than a touch of Marlene. However, the phrase “model turned…” is not for her, she says.

“As world-famous as she is, she’s nice to everybody, no matter who they are,” says Bobby Gillespie. “She’ll speak to somebody’s granny at a wedding.” His point was borne out by my many conversations about Moss. I don’t remember, as a journalist, writing about anyone else as powerful and famous who was like without exception or condition by everyone I spoke to, even if they were talking off the record, or who was praised as much by those she worked with. No one even seems to hate her because she’s beautiful or very rick. “She has zero vanity,” says Lucie de la Falaise.

I witnessed some of the fabled Moss stamina on my second day in France. The other guests, clearly hungover after their late night, were silent as we drove to the harbor for a boat trip down the coast. Moss was chirpy, lively, playing Family Fortunes, the board game, with Lila. As we sailed past Cap Negre, Moss and Lila danced together on the deck, shooting their arms in the air and singing:

Hands up, baby, hands up!

Gimme your heart!

Gimme, gimme your heart!

Gimme, gimme all your love!

They clearly have a symbiotic relationship. After Lila was born, Moss took her along on trips, and when the child started school, Moss limited her working trips away to three days. Bella Freud says, “She’s completely intrigued by Lila, always recounting stories about her observations. Once, when I was there, she spent the whole evening making this lovely card for Lila, because she would be gone by the time Lila woke up. People don’t see that side of her. You don’t get her going on about ‘all the things I do with my kid.’”

Amanda Harlech compares Moss to Daisy in The Great Gatsby, “but without the heartlessness. It was ‘Oh, come on, let’s have fun. Let’s just have fun.’ And that’s not frivolous, actually. To share happiness is the very noblest thing human beings can aspire to.”

I have witnessed the late-night entertainment, the steady buildup to some twirling and moving about, disappearing and reappearing with a change of look. It’s a floor show of sorts that is being prepared. “I used to do proper leaping, dancing, like Isadora Duncan,” she says. “Like that game of don’t touch the floor, leap, and if you can’t get from that table to that table, you have to get somebody to carry you, in a really theatrical way.” The other familiar moment known to Moss’s friends is when she starts talking to you close-up and almost inaudibly, her eyes fixed on yours, as if you’re being asked to lip-read, making you hang on to every word as you focus on the pointed, catlike incisors (without which, according to Marc Quinn, she wouldn’t be as big as she is now, since they give an animal rawness to the perfect face).

What is actually happening, according to James Brown, is that she gets so overexcited about telling a story that she has to run it in her head first. It’s a rehearsal.

Her friends know what it is like to be “Mossed.” You get home at nine a.m., usually regretting you had to leave. When Christy Turlington adopted Moss, she learned that “it’s never a night where it’s just hanging out at the hotel, watching TV. Everything can become the most fun, exciting night of your life.” Jess Hallett describes how she was persuaded by Moss to recuperate from illness at the Ritz in Paris. “I came back two days later with a black eye, broken finger, and I can’t even remember what else happened to me. My husband was like, ‘What have you done to my wife?’ We’d stayed up all the first night, and then she had to go to work. She said, ‘You’re not coming to work with me. You’ll give the game away.’ Because I was just so droopy-eyed.

“She got Mossed,” says Moss. “People that don’t know me get Mossed. It means, I was gonna go home, but then I just got led astray. In the best possible way, of course. I mean, it’s always fun, and a good time.” Hallett counters, “It can be a nightmare if you’re the only one there. ‘Please can we go home?’ ‘No.’”

Hallett describes a night in South Africa when Moss managed the impossible feat of getting Peter Gabriel to play and sing in her hotel suite after a party. “Oh, yeah, in Africa. That was insane,” says Moss. “That was a really good one. It was this show for Nelson Mandela, for the charity, and Richard Branson and Peter Gabriel came in, and I had a piano in my room, and I went, ‘Please, please, play that song!’ And he played ‘Don’t Give Up.’ I was dying! Then we just drank loads and loads of champagne.”

“I remember phoning downstairs,” says Hallett, “and saying, ‘Can we have an alarm call for seven a.m., please?’ They said, ‘That’s in five minutes, madam.’ And we had to wait for this jet, in this hangar in South Africa, in this awful heat. We hadn’t been to sleep. We were literally lying with our faces on the concrete, trying to keep cool.”

Marc Jacobs also got Mossed, at Moss’s wedding, to the rock musician Jamie Hince, in 2011. “I was supposed to have left a lot earlier than I did,” Jacob says. He ended up staying five days. “I couldn’t even remember the name of the hotel. You just don’t want to leave when you’re around Kate. You just don’t want it to end.”

Wife and Mother

In 2002, when Moss was pregnant with her child, by the magazine editor Jefferson Hack, she sat for the painter Lucian Freud. It came about, she says, because she did a questionnaire in i-D magazine. “It was like, Who haven’t you met that you’d really love to meet? And I said Lucian Freud. And within two days – I think Bella must have read it and told Lucian – she said, ‘My dad wants to meet you.’ And I was ‘Oh, my God!’ Bella said, ‘He just wants to go for dinner with you. Don’t be late.’ So I went to the house. She took me to the studio, and he started that night. Couldn’t say no to Lucian. Very persuasive.

And I phoned Bella the next day and said, ‘How long is it going to take?’ She said, ‘How big is the canvas?’ I said, ‘It’s quite big.’ She said, ‘Oh dear, could take six months to a year.’”

Freud demanded rigorous punctuality. The sessions were from seven p.m. to two a.m. three times a week, and toward the end, near Lila’s birth, four times a week. Moss never missed a session. Less well known than the portrait that emerged, is the fact that Freud tattooed Moss on her haunch, the upper part of her right buttock. Moss shows the tattoo to me in a restaurant, in a small outside smoking area at lunchtime – an extraordinary existential moment.

“Yeah!” she says. “He told me about when he was in the navy, when he was 19 or something, and he used to do all of the tattoos for the sailors. And I went, ‘Oh, my God, that’s amazing.’ And he went, ‘I can do you one. What would you like?’ I was like, ‘Really?’ He said, ‘Would you like creatures of the animal kingdom?’ I said, ‘I like birds.’ And he said, ‘I’ve done birds. I’ve got it in my book.’ And he pointed at a painting of a chicken upside down in a bucket. And I said, ‘No, I’m not having that.’ And then he said, ‘Maybe I should just do you.’ I thought, I’m not going to have a girl on my…So we decided to do a flock of birds, I mean, it’s an original Lucian Freud. I wonder how much a collector would pay for that? A few million? I’d skin-graft it. I think we should talk to [the art dealer William] Acquavella.”

There’s a moving photograph of a very pale, soon-to-die Freud lying in bed with Moss, his arm around her, taken by Freud’s assistant, the artist David Dawson, in 2010. “I went round with Jamie, and I took all these flowers, those little ones he loved, and we went over, and he was in bed, and he pulled back the covers and went, ‘I’ve been keeping it warm for you’. And I went, ‘Jamie’s here.’ And he went, ‘Oh, I see.’ He did like Jamie, though. I love that picture in the bed. It was Jamie’s suggestion that we take it. And I just got under his arm. Jamie’s in the reflection, sitting on the windowsill. Lucian was always really kind. I adored him.”

The pattern for Moss, when she takes public hits, is that after some bruising rounds she emerges stronger, more popular, more employable, and with more money. It’s as if these brushes with danger are what people expect of her, even like about her. In 2005 there was a harrowing pursuit by the tabloids and police when a video was sold, by someone close-up, apparently, showing Moss taking drugs. The police concluded that someone had deliberately tried to set her up, and in the end there was no evidence for a charge. But it took months out of her life. It was widely known that Moss took drugs, but as she admitted, disarmingly and unchallengeably, “I don’t take any more drugs than anybody else.” Label after label dumped its contracts with her, and for a while it looked as if the curtain might fall on her career.

The fashion industry largely supported her. Dennis Freedman continued to run cover stories on her in W. So did French Vogue. She got crucial support from Anna Wintour. And then, predictably, most of the labels came back. “I hired her at Calvin Klein right away again, to celebrate,” says Fabien Baron. “She did the right thing – went to rehab, cleaned herself up. She had to. She had no choice.”

Moss won’t talk about the incident except to say of Wintour, “There are people who will not let the side down, no matter what the press says. One is Anna. She is proper. She will fight for you even though she doesn’t have to. She’s really taken care of me. If I called her crying, she would always pick up.”

Moss met Jamie Hince in 2007, in what sounds like random computer dating. It turned out that, apart from being a very talented guitar player for the Kills, his band with singer Alison Mosshart, he had brains and a surreptitious sense of humor, including a good line of takeoffs and impersonations – just the right armor for the storm he was about to enter. He sits coolly and quietly in its eye.

“Jamie’s amazing,” says Moss. “Basically, he turned up. I was at Lucie’s house in the South of France, and we were Googling men. And I went, ‘Ooh, I like the look of him.’ A friend set us up. He turned up, and we spent, like, the next four days together. And after we finally woke up, I said, ‘Do you want a bacon sandwich?’ And he just laughed at me. I didn’t know he was a vegan. We’d been together four days. He wasn’t a vegan for much longer. I did get him with the bacon sandwich.” I ask if they fell in love immediately. “Yeah. He likes to do the same things that I like to do, and he’s got the same sense of humor. He’s really fun. And really grumpy as well. Men are grumpy, aren’t they?”

She takes me on a tour of the Georgian brick house in Highgate where she and her small family live and shows me the room Samuel Taylor Coleridge occupied for the last few years of his life and the garden below, where, toward the end, he would stroll with Thomas Carlyle. The house belonged to a doctor who was treating Coleridge for laudanum addiction. “So I’ve moved into a rehab,” says Moss, laughing.

George Michael, her neighbor down the road, says, “I think she lives her life as she wants to live her life. And I think that appeals to a lot of people, the idea that she has the opportunity to have fun with her life and she does it.”

Did those 25 years feel like a long time? Does she feel like a rest? “It doesn’t seem like that long to me,” she says. “It doesn’t feel like, Oh, my God, I’ve been doing it that long. I don’t really feel old – that’s for sure. There are a lot of girls around that are really cool, Alice Dellal and Lara [Stone], Georgia May – she’s so cute. There’s all the cool girls, and I know who the cool girls are. So I definitely know what’s going on, even though I’m probably a lot older.” Why wouldn’t she know what was going on?, I ask. “I don’t know,” she says. “I don’t really go to clubs anymore. I’m actually quite settled. Living in Highgate with my dog and my husband and my daughter! I’m not a hell-raiser. But don’t burst the bubble. Behind closed doors, for sure I’m a hell-raiser.”